In the previous post, I wrote about the illustrations in the British and American version of The Strange Library. The story came out in German a year earlier, in 2013, in Ursula Gräfe's translation, Die Unheimliche Bibliothek, illustrated by Menschik. Menschik had earlier done the illustrations for three other Murakami stories: Schlaf ("Sleep," 2010, translated by Nora Bierich) and Die Bäckereiüberfälle (which consists of two short stories, "The Bakery Attack," and "The Second Bakery Attack," 2012, translated by Damian Larens). While the first of these (The Strange Library/ Fushigi na Toshokan) was also an illustrated book in Japanese, the other three stories were not, and appeared in short story anthologies.

It would be worth thinking about the relationship between illustrations and the translated text: What new qualities do they add to the story? Do they detract from the story or help us enjoy it more? Do they make concrete something the author intended to leave vague? In the case of stories that were originally accompanied by illustrations, why not use those? Do illustrations have to be "translated," too? In the case of stories that originally lacked illustrations, what does it mean to add that element?

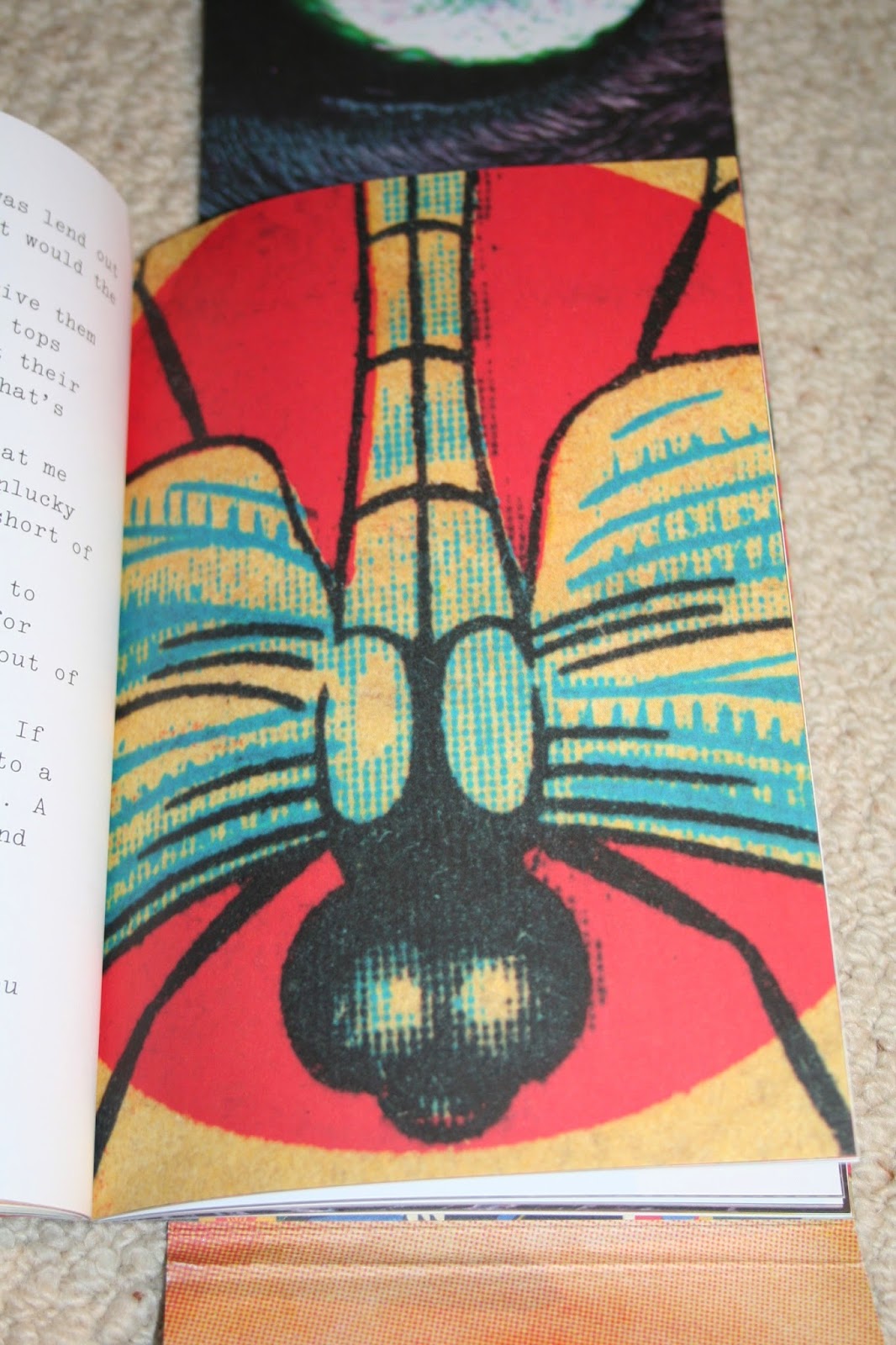

Menschik's illustrations, as is already clear from the cover of the Die Unheimliche Biblioteque, are quite different in style from the original ones by Maki Sasaki. Below left is a picture showing both editions of The Strange Library. On the right is an illustration of the German version of Sleep, which was not illustrated in the original.

All three stories were re-published in Japan with Menschik's illustrations. What is interesting is that the title of the Strange Library went back to the original 1982 title, Toshokan kitan (Strange Tales of a Library), and the title of Bakery Attacks ("Pan'ya Shūgeki" and "Pan'ya saishūgeki") became something like "To Attack a Bakery (or Bakeries)" ("Pan'ya o osou"). It may be the case, of course, that the Japanese version IS in fact a new edition of the original story, which was much longer. (I will order it and report.) Below are the only two illustrations included with "Toshokan kitan" in the 1983 anthology, titled Kangarū-biyori:

Below are the covers of the Japanese editions of Toshokan kitan (2014, Strange Tales of a Library), Pan'ya o osou (2013, To Attack a Bakery) and Nemuri (2010, Sleep), all with Menschik's illustrations:

Menschik's illustrations clearly are admired by many, since the Spanish edition of the Strange Library (or rather: Secret Library) (2014, Lourdes Porta, tr.) and the French edition of Bakery Attacks (2012, Corinne Atlan, Hélène Morita, tr.) also used her images:

The same is true of the story Sleep, which came out with Menschik's images in French (2010, Corinne Atlan, tr.), Spanish (2013, Lourdes Porta, tr.), and Italian (2014, Antonietta Pastore, tr.) It is worth noting that in both Spanish translations Lourdes Porta got her name on the cover!